Wilfred Thesiger in Africa: A Centenary Exhibition

Probably the greatest traveller of the twentieth century, and one of its greatest explorers, Sir Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003) is most famous for his journeys in Arabia and his sojourns among the Marsh Arabs in Iraq. Yet fifty of Thesiger’s seventy years travelling, exploring and living in remote places were spent in East and North Africa. Born in Addis Ababa, where his father served as British Minister in charge of the Legation, he lived there until 1919, when his family returned to England. Longing to return to Ethiopia, in 1930 Thesiger received a personal invitation to Ras Tafari’s coronation as Emperor Haile Selassie, and his life of travel and adventure had begun.

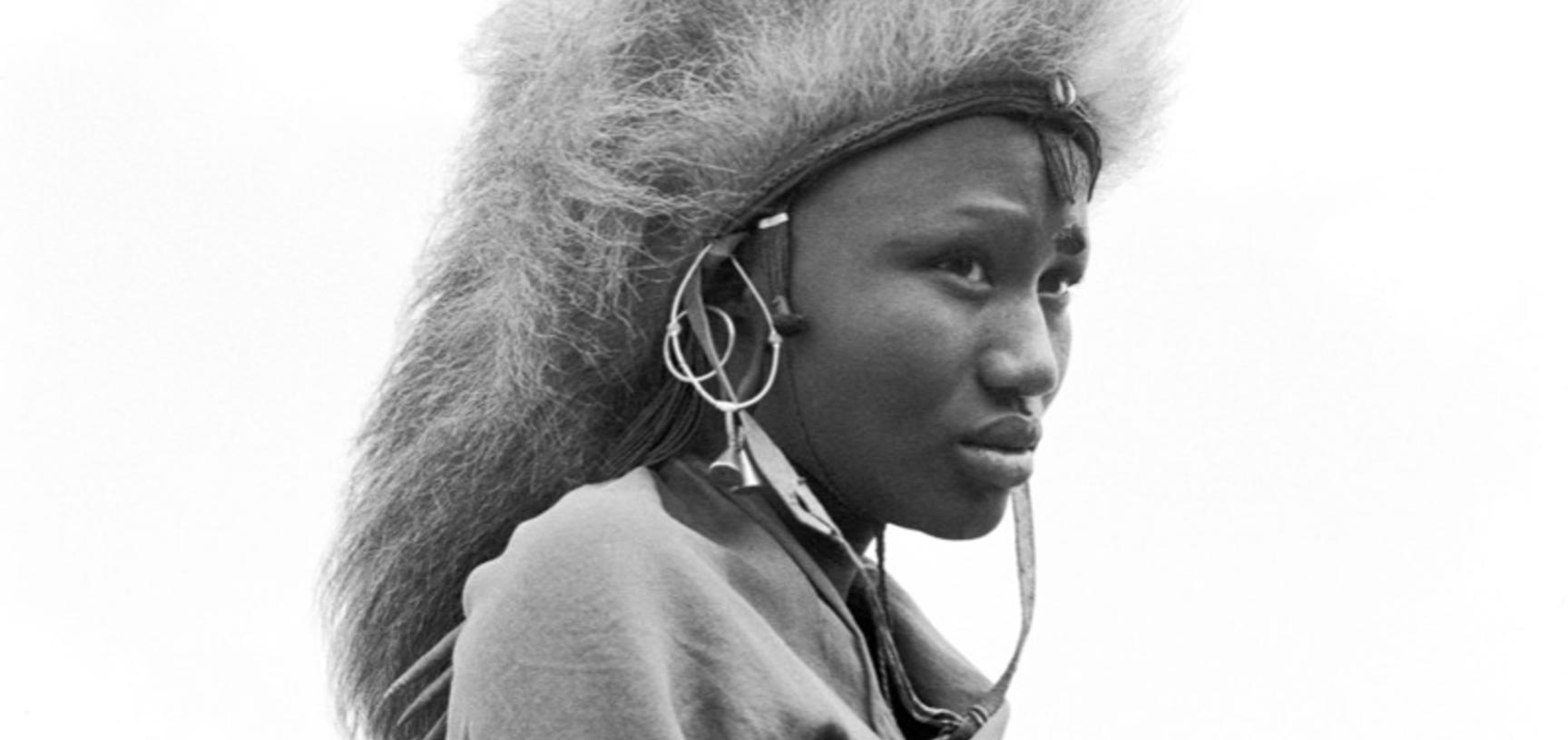

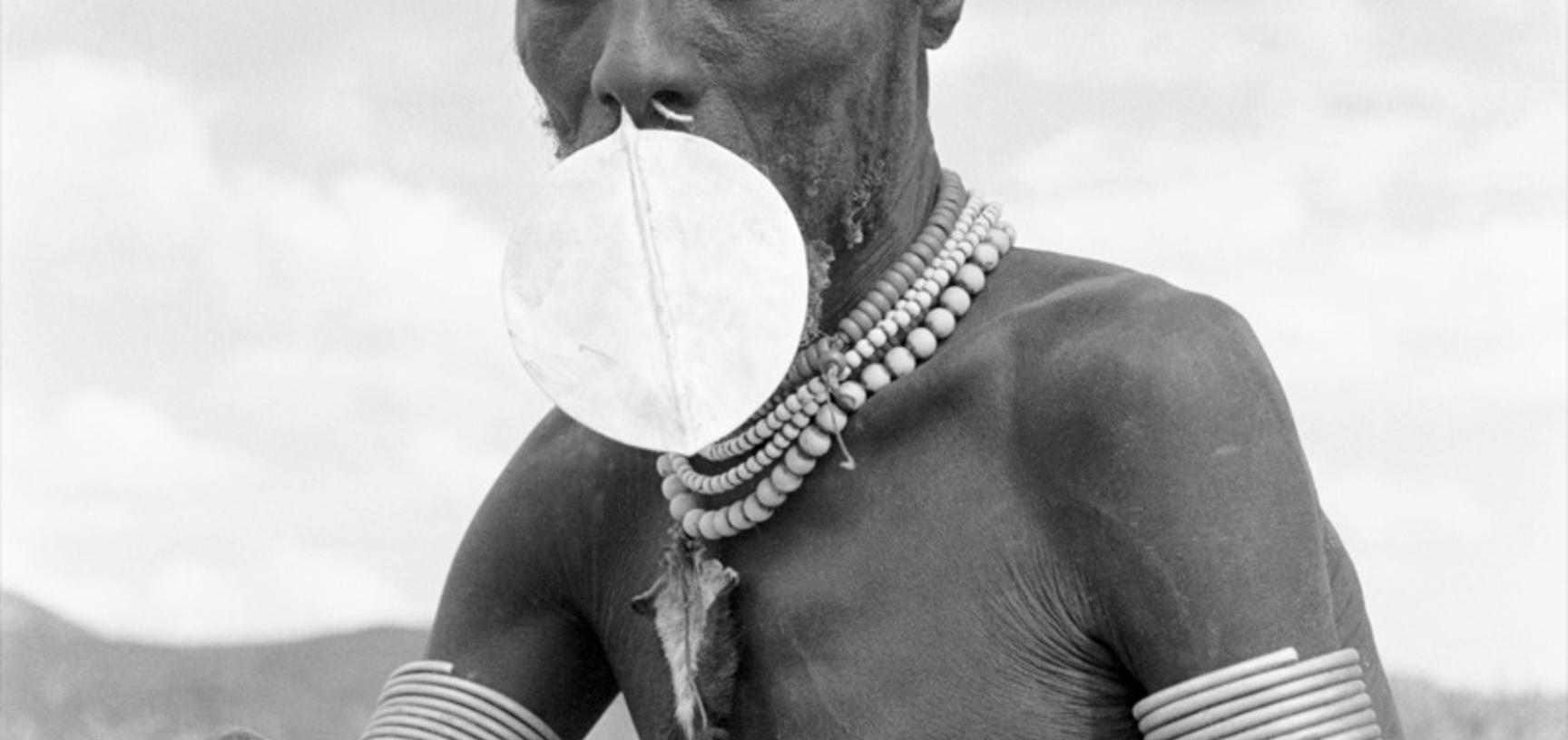

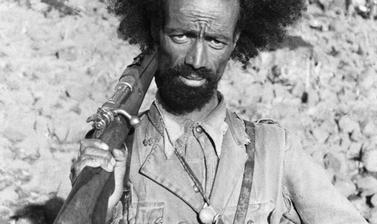

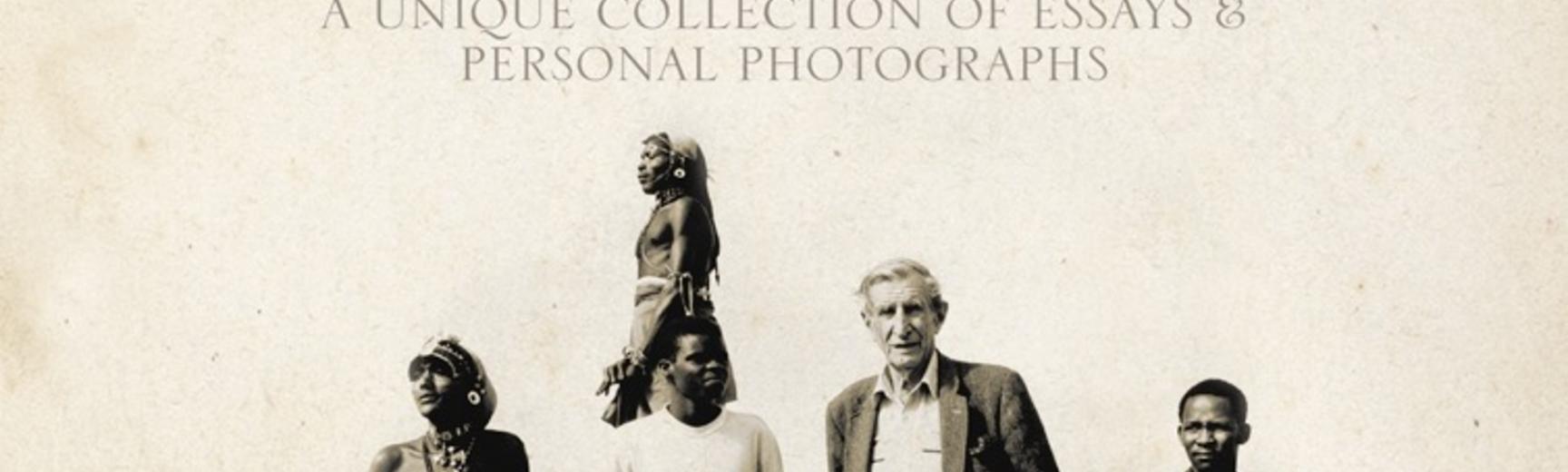

This exhibition is the first to explore Thesiger’s lifelong relationship with Africa. He undertook river explorations, wartime service and travels in Ethiopia, political service in the Sudan, travels in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, and numerous journeys on foot in Kenya and Tanzania. From 1978 Thesiger lived for nine months of each year in Maralal, Kenya, before retiring permanently to England in 1994. Wilfred Thesiger took over 17,000 photographs in Africa, around two-fifths of his entire photographic output, all of which he donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum. Spanning fifty years, the photographs exhibited here document his development as a photographer, in particular as a portraitist. ‘Ever since my time in Northern Darfur,’ Thesiger wrote, ‘it has been people, not places, not hunting, not even exploration, that have mattered to me most.’ Although also known for his romantic landscape images, Thesiger saw these as secondary, ‘a setting for my portraits of the inhabitants’.

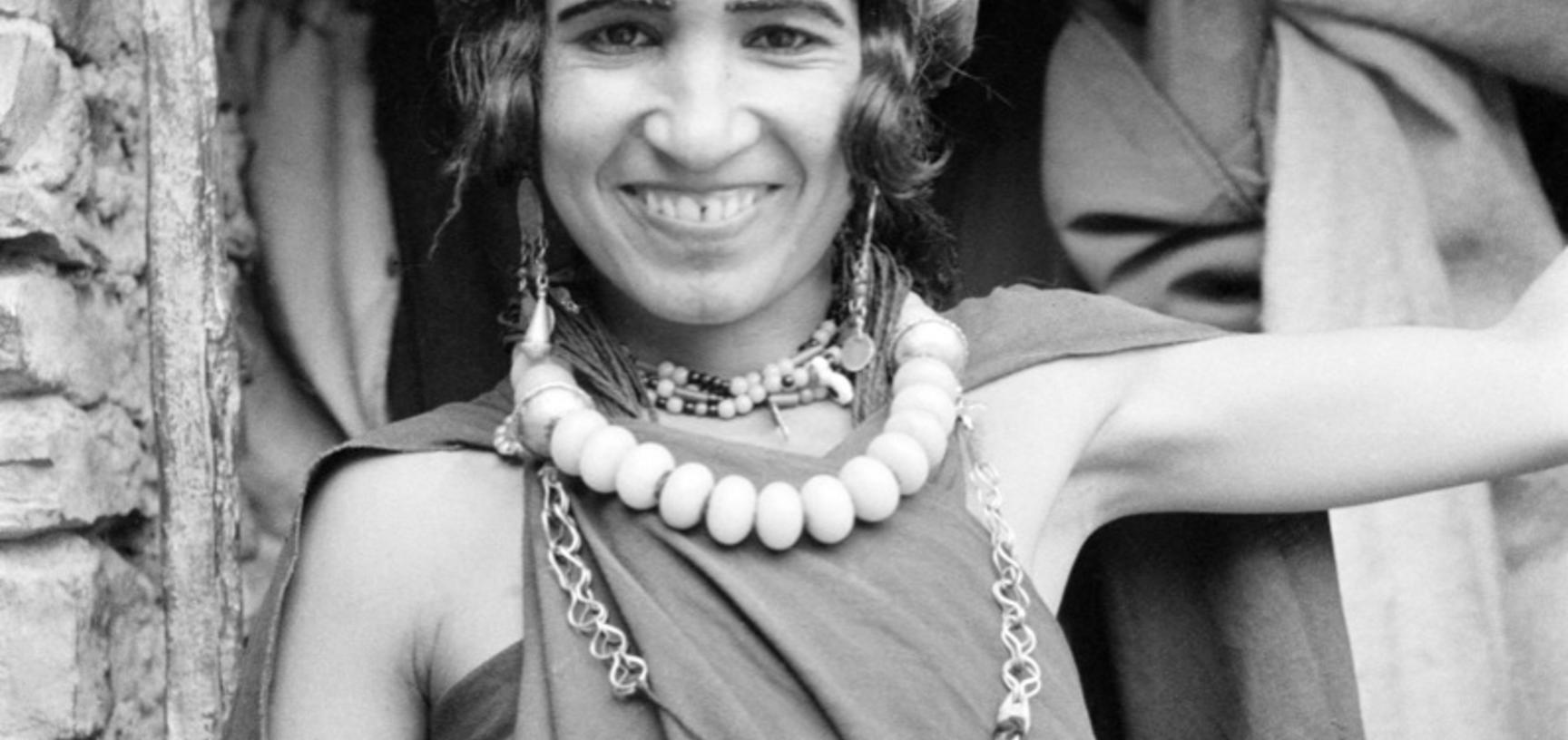

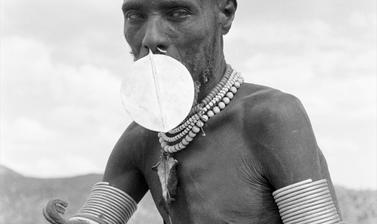

This exhibition is also a celebration of the people Thesiger photographed and the diverse cultures they represent. From the Afar (Danakil), Konso and Boran of Ethiopia, the Nuer and Dinka of Sudan, the Berbers of Morocco, and the Samburu and Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania, this exhibition offers historical glimpses of some of the most fascinating cultures and places on the African continent.

Ethiopia (Abyssinia)

Thesiger’s father, Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger, was appointed Consul-General in Addis Ababa in 1909. The ten years that the family were to spend there was a tumultuous period in Abyssinian history. In 1916 Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger sheltered Ras Tafari’s infant son during the rebellion that ousted the heir apparent to the Ethiopian crown, Lij Yasu.

It was partly this act of support by Thesiger’s father (who died in 1920) that led to Ras Tafari’s personal invitation to Thesiger to attend his coronation as Emperor in 1930. This event gave Thesiger his first opportunity to hunt and explore in the country of his birth, and in particular to follow the Awash River to its end – the last geographical puzzle in Abyssinia, and a chance to make his name.

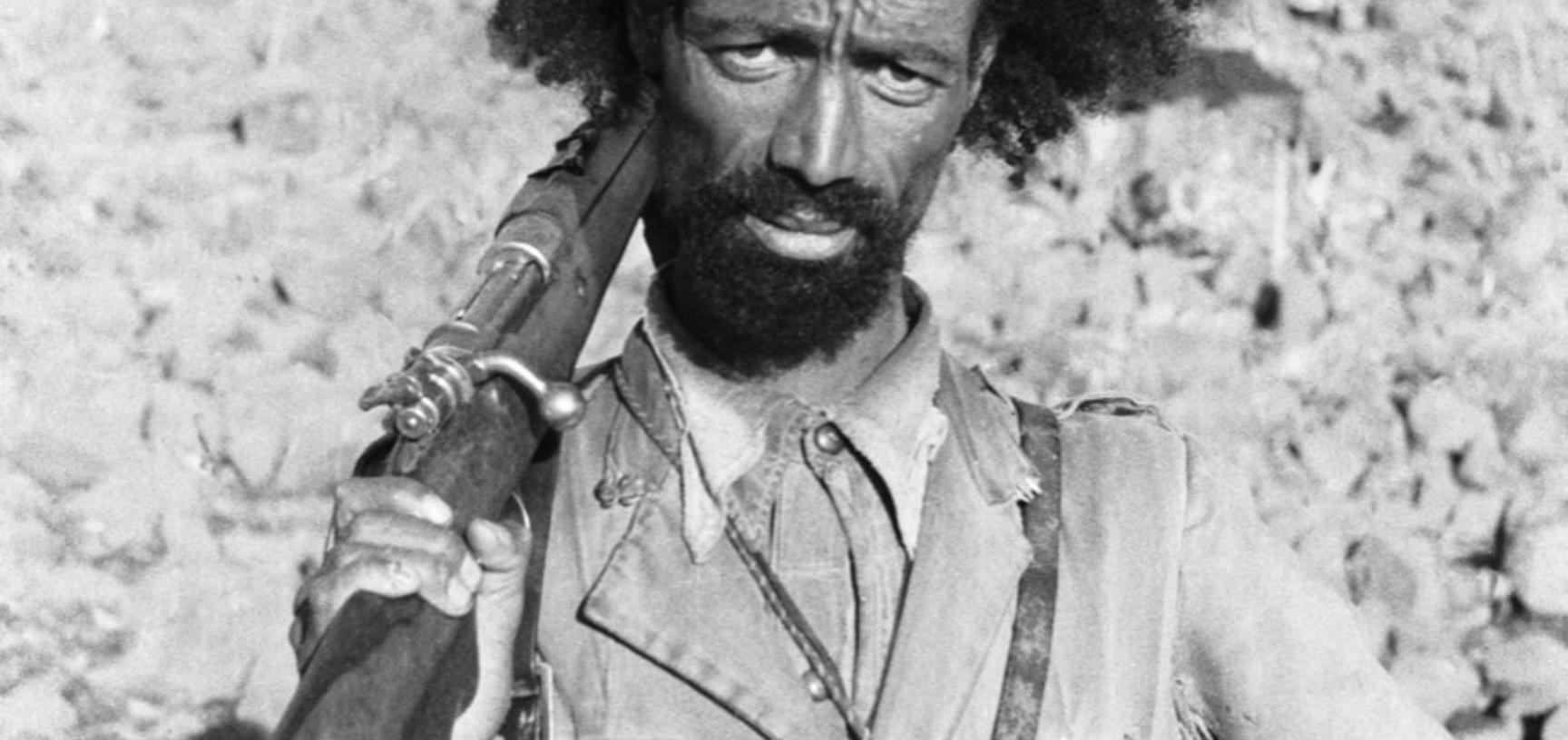

Horrified by the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, Thesiger served under Orde Wingate and alongside local resistance fighters (dubbed ‘Patriots’) to liberate the country during the Second World War, being awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1941 for his part in the capture of Agibar.

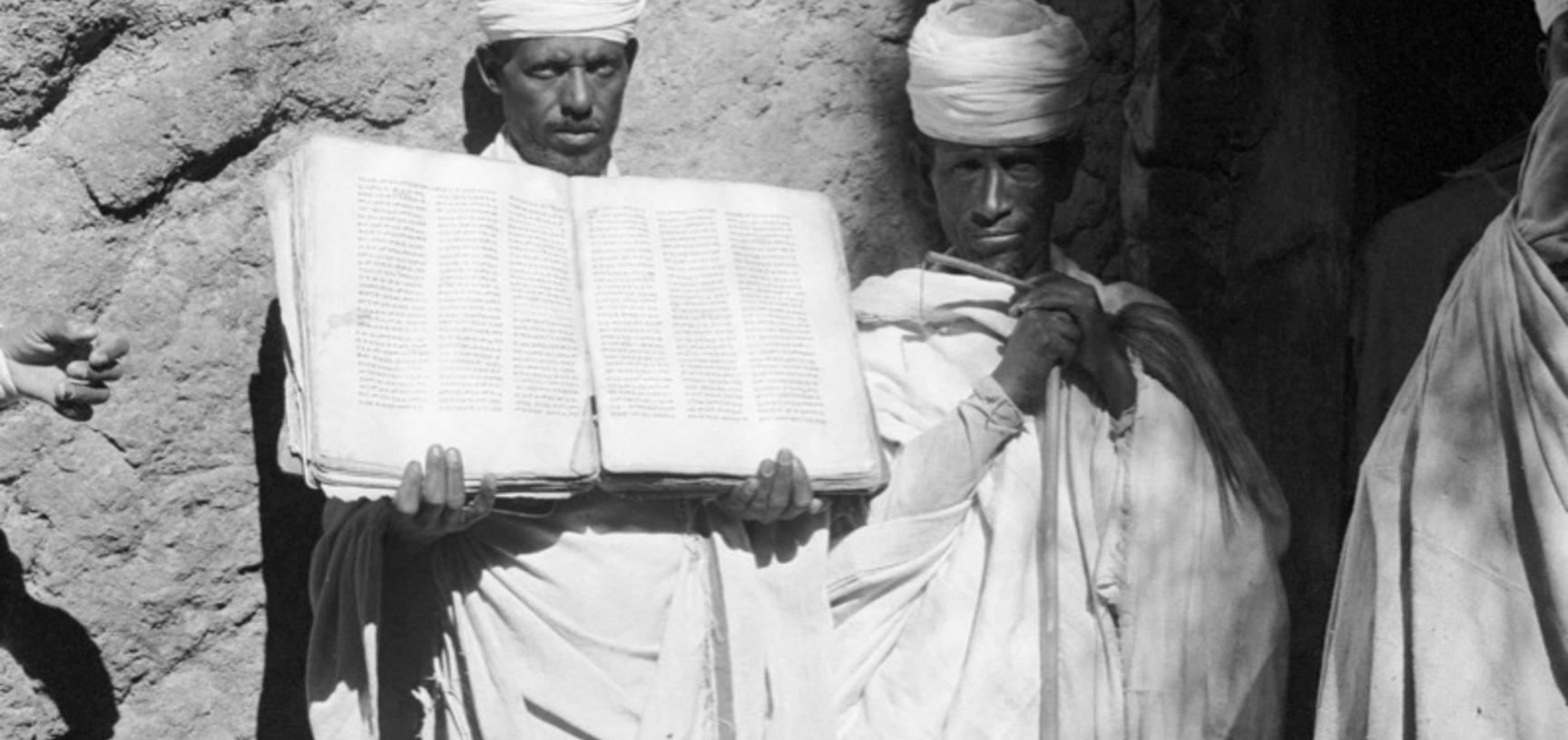

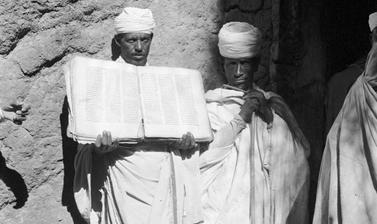

After a brief, but frustrating, stint in 1944 as Political Adviser to the Ethiopian Crown Prince, Thesiger was not to return to Ethiopia until 1959, when he travelled on foot as far south as the border with Kenya, and then made a great circuit of the north. During this time he was at last given permission to visit Lalibela, with its unique rock-hewn churches. In the south of the country he photographed Konso villages with their extraordinary carved grave monuments honouring the dead.

Wilfred Thesiger’s photographs of his Awash River expedition were taken with an old box-camera (with a damaged viewfinder) that had belonged to his father. But having honed his photographic eye in Arabia and Iraq in the intervening years, the images that he took with a Leicaflex camera on his return to Ethiopia in 1959 show how skilled a photographer he had become, and how seriously he had come to take the medium as a record of travel.

Sudan and Morocco

By the age of thirteen, Thesiger had decided that his future lay in the Sudan Political Service. This was largely because of its proximity to Ethiopia, where he really wished to be, but also due to its big game and diverse population. Accepted into the Service in 1934 – partly, he felt, due to the success of his Awash River expedition – he was posted to Kutum in Darfur, where he at last lived the sort of life he had dreamed of: hunting, travelling by camel, and living with native people in a desert landscape.

At Kutum, Thesiger heard about a fourteen-year-old boy called Idris Daud, who had been imprisoned after stabbing another boy in a scuffle. Thesiger paid the blood-money owed to the victim’s family and set him free. Idris became Thesiger’s loyal companion, and went with him when he was subsequently posted to Nuer country in the south in 1937. Here again Thesiger spent much of his time hunting, joining the Nuer on their hippo hunts and shooting lion.

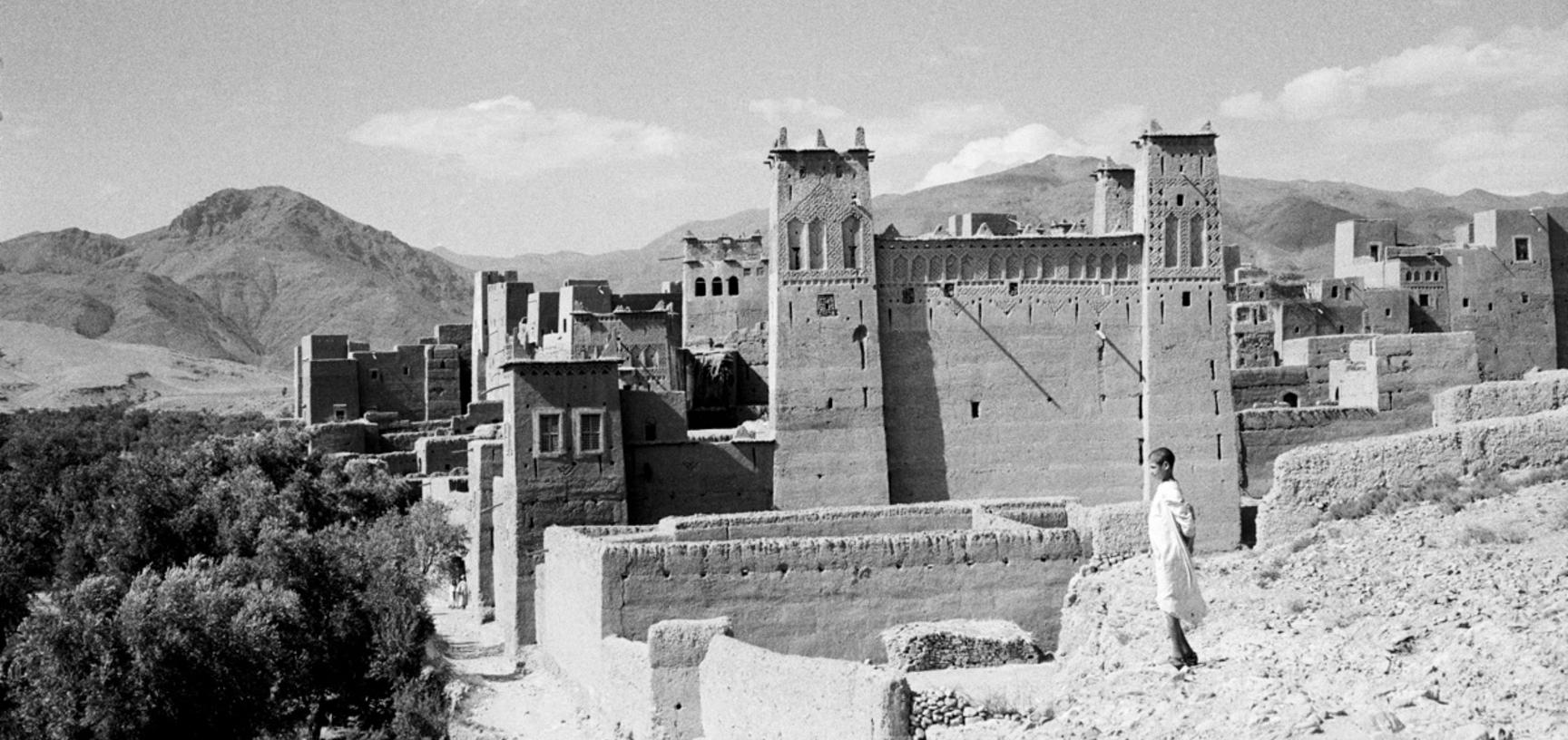

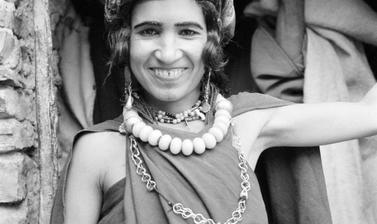

Thesiger first visited Morocco in 1937 with his mother. At Telouet (in the High Atlas Mountains), the Pasha of Marrakech, Thami al Glawi, gave them a banquet in his spectacular kasbah. In 1955 Thesiger returned to spend a further two months trekking and climbing there, even encountering an Oxford University Expedition that had come to study a Berber village. Between 1965 and 1969 Thesiger would travel for two months of each English winter in Morocco with his mother, then in her eighties but as hardy as her son.

Thesiger barely mentions his Moroccan travels in his writings, but his photographs are a revelation; extraordinary landscapes, views of remote settlements and striking portraits document a way of life yet to be affected by encroaching westernization, the first signs of which were the telephone lines linking kasbahs to the towns.

Kenya and Tanzania

Thesiger first visited Kenya in 1960 with his friend Frank Steele, making a journey on foot in the Northern Frontier District, from Isiolo as far as Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana). Reminiscent of his arrival at Lake Abhebad in Ethiopia nearly thirty years earlier, Thesiger felt a sense of achievement: ‘Suddenly, it was there below us. Few other sights have made a greater impact on me.’ Thesiger’s other Kenyan journeys, however, were made without any definite geographical objective (apart from his mountain ascents), often crossing the same territory year after year with a few local guides and camels, continually on the move for eight or nine months. He was to spend much of the next thirty-five years travelling, and eventually living, in Kenya’s Eastern and Rift Valley Provinces.

In April 1961 Thesiger travelled in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) with another friend, John Newbould, the pair walking for a month around Ngorongoro Crater with donkeys hired from local Maasai. For Thesiger, the Maasai embodied traditional Africa, yet he feared for their future: ‘They have scorned everything which the West has offered them, and how right they are. The tragedy is that others who have not… are bound to win in the modern world, though they lose their souls in the process.’

After many years travelling in the company of Samburu youths, Thesiger came to understand the importance that they attached to their initiation as moran, or adult warriors, through circumcision – something that he had gained experience of among the Marsh Arabs in Iraq. Considering it overlooked in most academic studies, he made careful notes and photographed the rituals and ceremonies associated with circumcision, ‘the most important in the lives of the Samburu’.

Kenya, My Sanctuary

“It is here, among those whose lives I share today, that I hope to end my days.” — Wilfred Thesiger, 1994

Sadly, this was not to be. Shortly after these words were published, both Lawi Leboyare and Laputa Lekakwar, Thesiger’s two closest Kenyan companions, died within six months of each other. Aged eighty-four, and with no one to look after him, Thesiger reluctantly decided to return to England.

From 1978 to 1994 Wilfred Thesiger had lived for nine months of the year near Maralal with Lawi Leboyare, the Samburu youth he had first met at Baragoi where Lawi attended the local primary school. As mzee juu, or senior elder, Thesiger was accorded paternal status by the Samburu, who attached great importance to the bond between father and son. It is one of the paradoxes of Thesiger’s character that he was to spend large sums of money on the material aspirations of his adoptive families in Maralal, while at the same time decrying the destruction of their traditional culture.

Yet the ‘traditional’ pastoral life that attracted Thesiger to Maralal was a world from which many younger Samburu dreamed of escaping. Lawi, who respected Samburu tradition, yet found western innovations irresistible, called Thesiger ‘Old Stone Age’. This appealed to Thesiger’s sense of humour, since it seemed to encapsulate the different world-views of Lawi, who saw himself as ‘modern Man’, and his own romanticism about the past.

Thesiger felt bound to do whatever he could to help the young Samburu close to him survive and prosper in a changing world. Though he would remain ambivalent about the sort of influence he had had on their lives, he refused to accept that his efforts to help had been in vain: ‘Their standards are different from ours. You can’t begin to compare them. I was an utter fool, I suppose, but personally I don’t regret any of it….’

https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/195658761&color=%2379844f&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true&visual=true

Acknowledgements and Credits

- Exhibition curated by Christopher Morton and Philip Grover

- Negatives scanned and enhanced by Adrian Arbib, Arch Image

- Photographs printed by Malcolm Osman

- Framing by Isis Creative Framing

- Print design by Claire Venables, Giraffe Corner

- Special thanks to Benedict Allen, Sir David Attenborough, Jeremy Coote, Elizabeth Edwards, Schuyler Jones and Alexander Maitland

- Supported by the William Delafield Charitable Trust

You can read an article by co-curator Philip Grover on the reasons for the centenary exhibition’s central focus online here (Royal Photographic Society Journal).

You can listen to a lecture by Alexander Maitland, writer and official biographer of Sir Wilfred Thesiger, elaborating on the subject of the Pitt Rivers Museum’s centenary exhibition, ‘Wilfred Thesiger in Africa’, online here (SoundCloud/PittRiversound) or above.

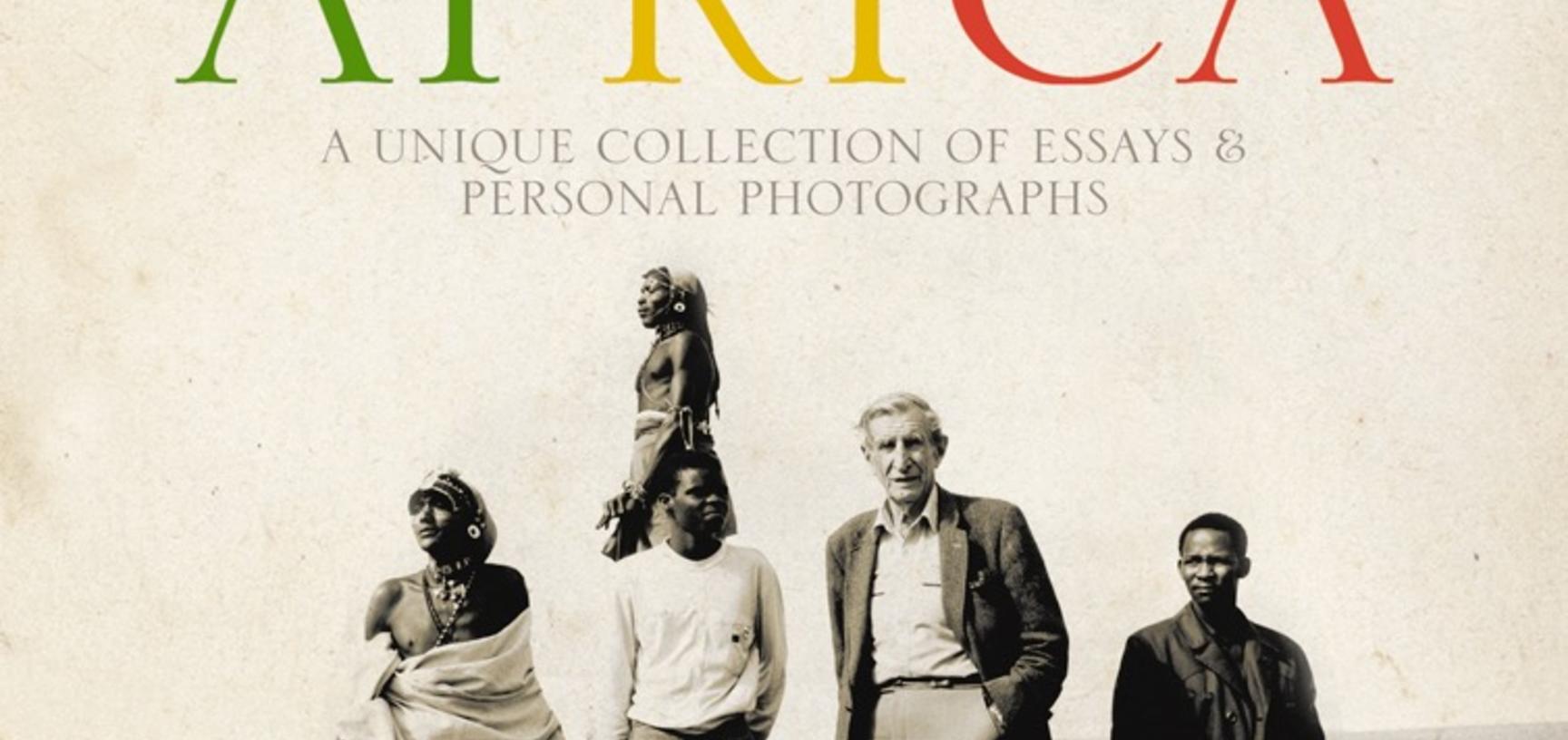

A new book has been published to accompany the Pitt Rivers Museum's exhibition: Christopher Morton and Philip N. Grover (eds.), Wilfred Thesiger in Africa (London: HarperPress, 2010). You can watch an endorsement of the companion volume by contributing author and biographer Alexander Maitland online here (YouTube/HarperPress). You can order the book online here (University of Oxford Shop) or below.

You can order a selection of reproduction prints from the Pitt Rivers Museum’s Wilfred Thesiger collection online here (Pitt Rivers Museum Prints/King & McGaw).