Memoirs in My Suitcase

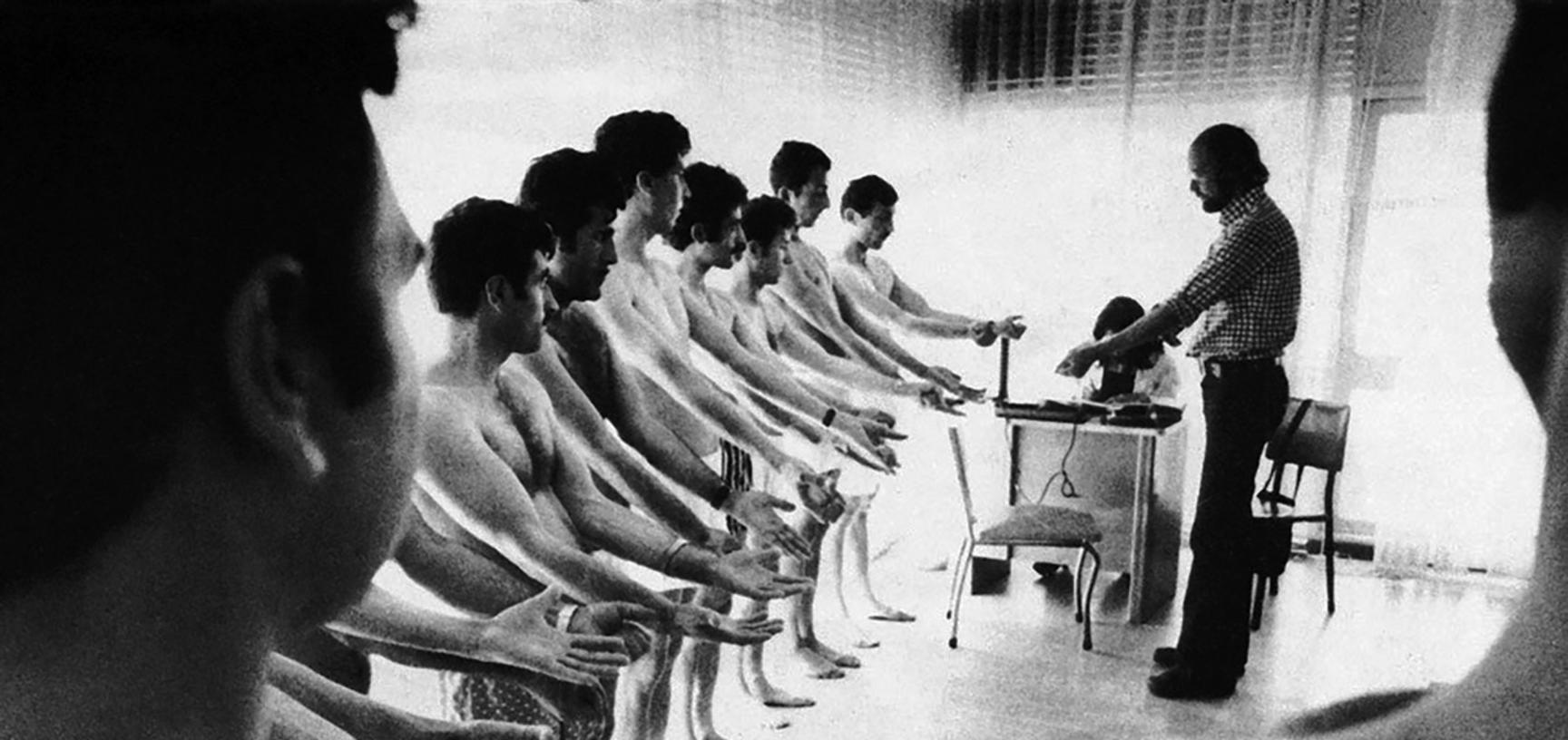

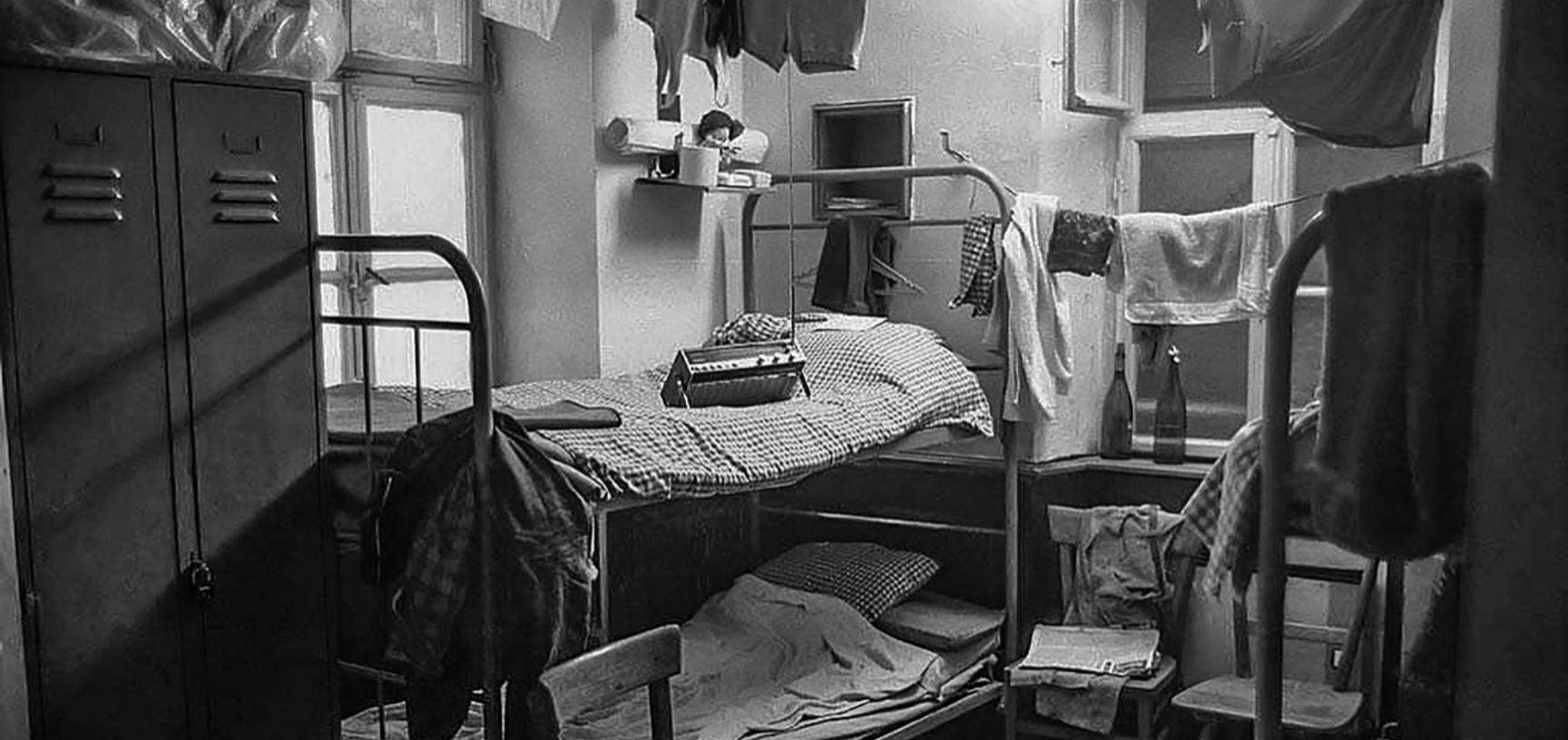

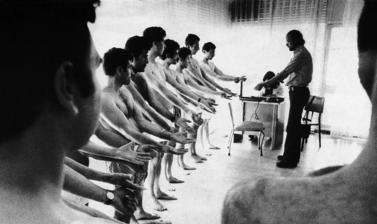

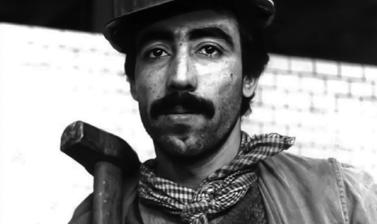

Among those travelling abroad to meet the labour needs of Europe in the 1960s were many Turks. In Germany they were called ‘Gastarbeiter’, i.e. guest workers. They were supposed to work in the country for a few years, to save money for their families, and then return home. Workers underwent rigorous health inspections (too demeaning for tourists), and they put up with this in order to earn money to pay for their wedding, to be able to buy a tractor, or to send wages back to their hometown. But this was not the only hardship which those who went would have to endure: a train journey that took three days and two nights, the worker dormitories which slept eight to ten people and dated back to the war years, difficult working conditions, and a foreign environment with different language, lifestyle, traditions and culture were just some of the challenges of their new lives.

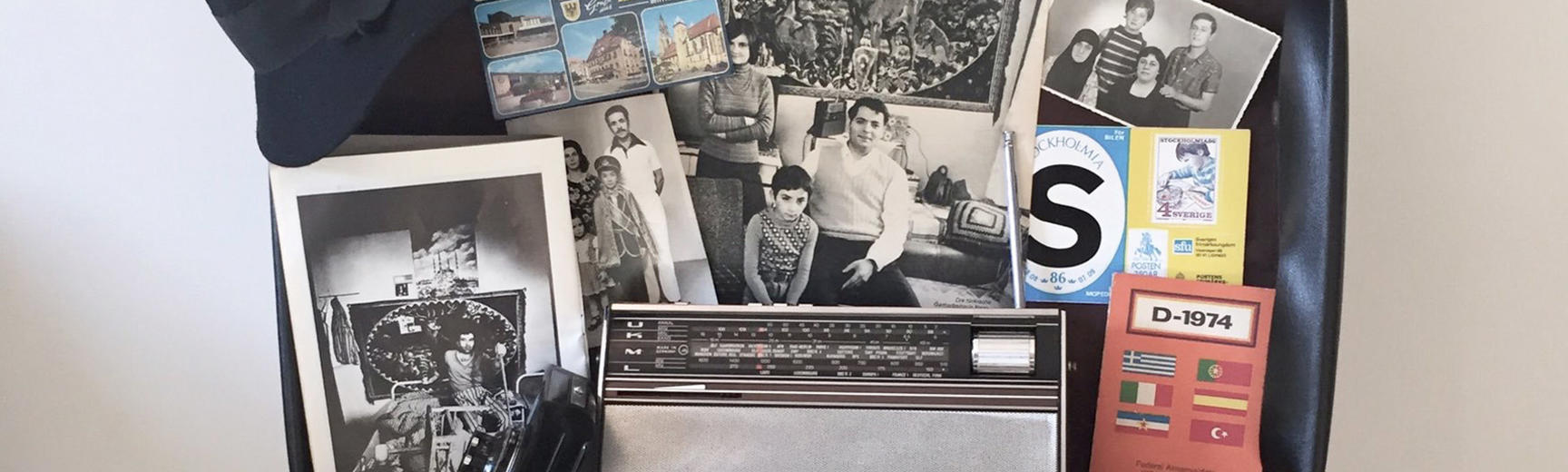

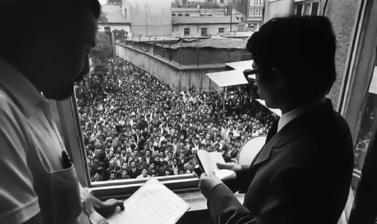

None of this, however, prevented a steady increase in the number of trains filling up and departing from Istanbul station. At first the worker trains departed only twice a week. Then they became as frequent as every day, and even twice a day, transporting Turkish workers to jobs in the mines and factories of Western Europe. In this way, hundreds of thousands of people who did not know each other came together, bound by the same fate. Suitcases, tickets, food packages, water flasks, family photographs, and so much more: the everyday lives of workers converged on these objects of immigration. Many letters were written and many cassette tapes were recorded. Poems and songs kept them company.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/j1fn4y46czc

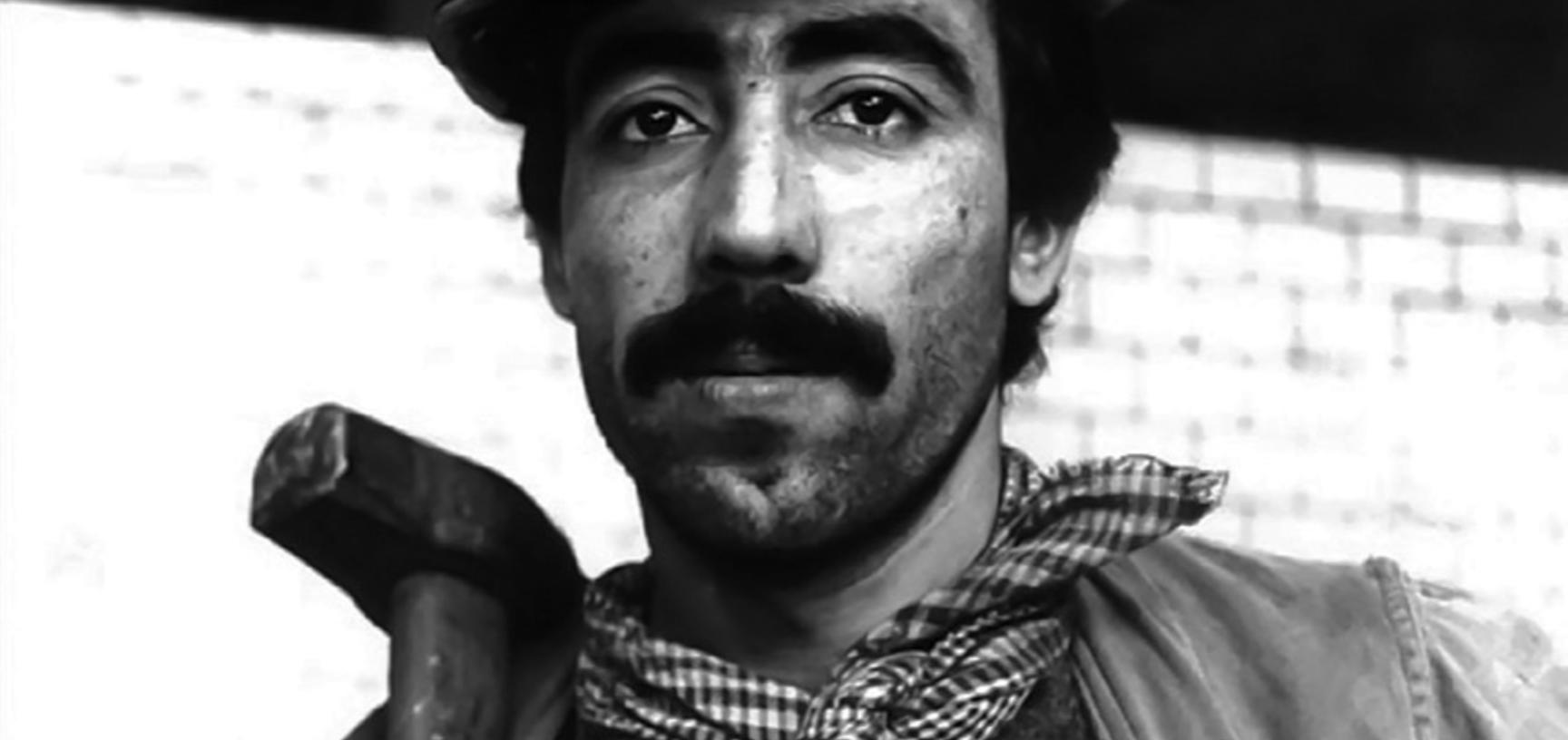

‘Mustafa – Misafir İşçi / Guest Worker No. 569716’, a BBC documentary programme (1973) about Turkish migrant workers, or ‘Gastarbeiter’, in West Germany (BBC News Türkçe/YouTube).

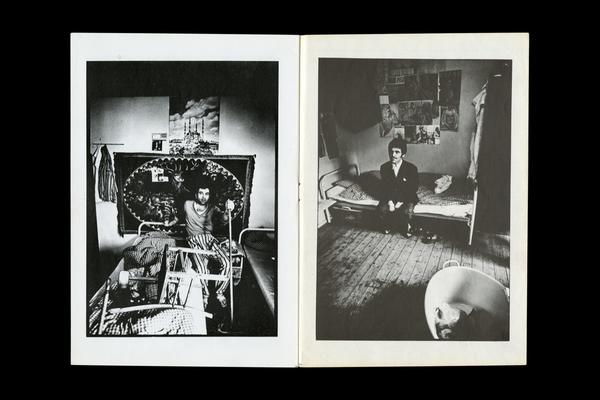

Although the dream of returning to the homeland always persisted, it was not easy. Many of those who went abroad stayed there. They took their families with them and settled in the countries where they had found work. New generations were raised in the languages of both their country of origin and the host country. The immigrant families of Europe lived in cheap and dilapidated housing. In fact, districts like Kreuzberg in Berlin came to be known as ghettos. Reminiscent of the darkest times of World War Two, the word ‘ghetto’ was also used for immigrant housing. What had started as guest-host relationship continued in the ghetto, exacerbating racial tensions that have been on the rise ever since.

Life went on. As the immigrants started small businesses like shops, restaurants, cinemas and offices, as well as mosques, schools and language courses, the number of permanent settlers increased. In the 1970s, following the world oil crisis, West Germany stopped recruiting workers; and in the 1980s laws incentivising a return to the homeland resulted in thousands of Turkish families going back to Turkey. Nevertheless, many more people in these communities preferred to stay in Germany and other European countries. By this time the idea of ‘homeland’ had become mainly a holiday destination in the summer months. Europe was their second home now, the place where they would live and die.

The guest workers setting out with suitcases from Sirkeci Railway Station in Istanbul in the 1960s led the way for the Turkish diaspora, which today numbers 6.5 million people. This is our story; it’s the story of our people.

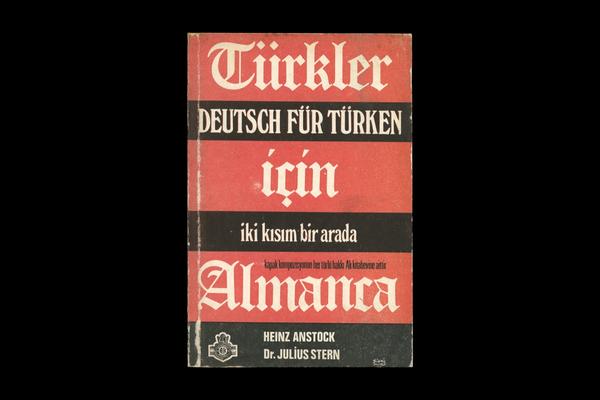

The Journey

- Guide-books and Dictionaries: Those who passed the physical and psychological tests, and therefore became eligible to be ‘guest workers’, waited for the day of departure with their train tickets in readiness. Some tried to learn a few things about a country which they could not locate on a map by reading guide-books. Others tried to learn some German so that things would become easier later on. Guide-books and dictionaries used to sell well around the railway station. Guest workers wanted to find out where Germany was, what the country was like, what to eat and drink, and so on.

- Advice: The first generation of Turks to go abroad as guest workers were seen as representatives of their people. They therefore had to dress well, speak well, and be worthy of their country. İŞKUR (Turkish Employment Agency) organised the departure and handed out printed advice sheets before workers boarded the train, asking them to retain the information after the journey. The advice covered subjects such as combing one’s hair, eating with a knife and fork, writing letters home regularly, cutting one’s nails, being punctual at work, and going to bed early at night. Just like a mother’s advice, the workers kept it in mind.

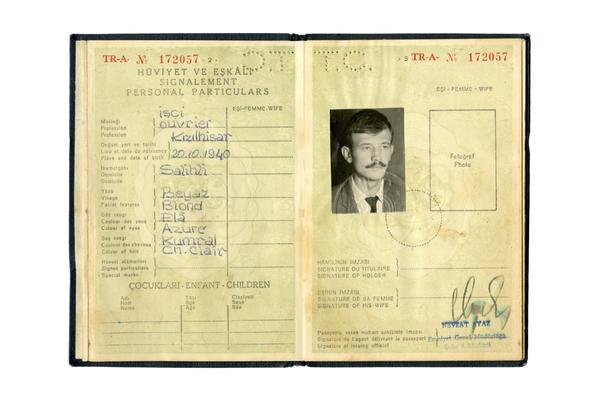

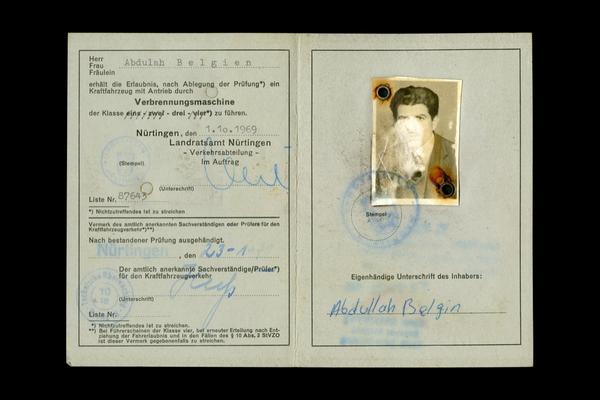

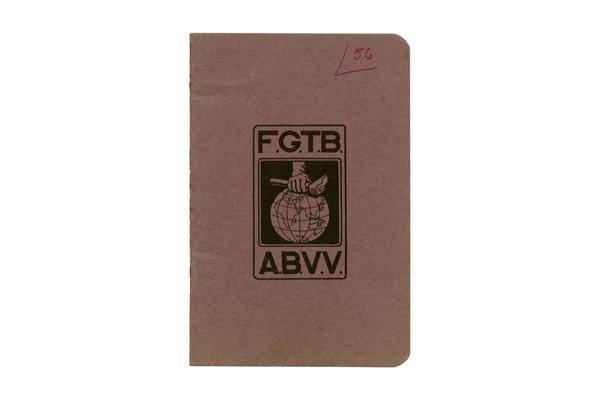

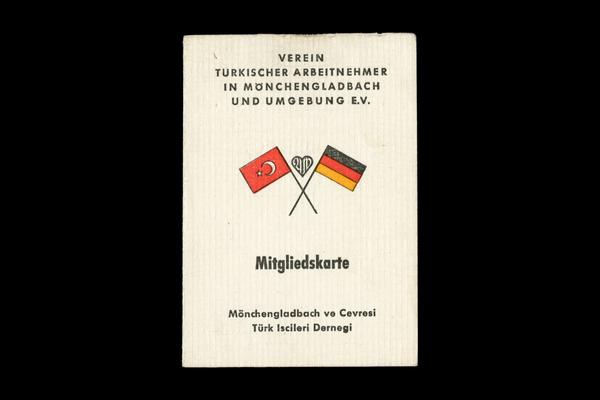

- Identity Documents: ‘It’s been many years. They ask me if I got used to this place. I tell them from the very first day on, I always carried my passport with me. That’s how much I got used to this place.’ A retired worker who lived abroad for about thirty years said this. Identity cards and passports signify so much more than just papers. A factory identity card or trade union card, or a passport with work and residence permits tucked inside, mean freedom to roam the streets. An identity card is not just an identity card for an immigrant worker; it is the key to freedom.

“When my husband said he was going to Germany, I never said anything. I had heard its name for the first time. I realised how far he was going away from me when he said the train journey took three days.”

The Suitcase

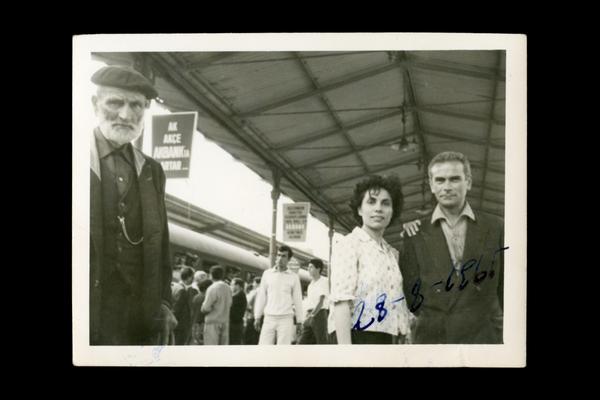

- Passengers: Some stations are always remembered with sorrow. One of those places is Sirkeci Railway Station in Istanbul. When it first opened in 1872, nobody could foresee that it would become a ‘station of farewells’ in the future. However, in the 1960s every worker going abroad from Turkey boarded a train at Sirkeci Station. Since workers saw their families and loved ones for the last time here, it came to be called the ‘Capital of Goodbyes’.

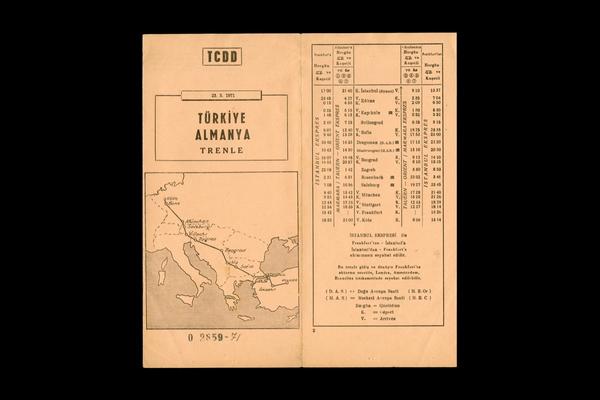

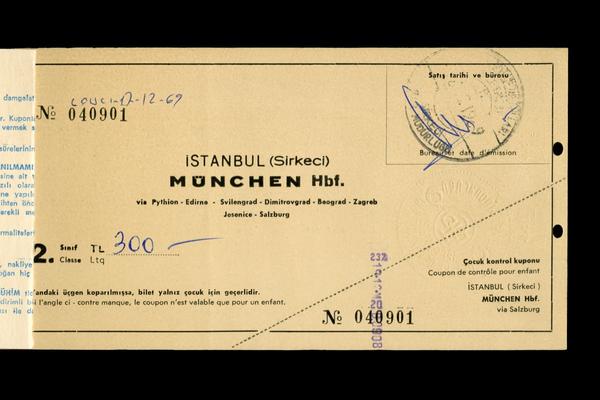

- The Itinerary: The train journey from Istanbul to Germany – which took three days, two nights, and more than fifty hours – is etched on every worker’s memory. Even after fifty years people can remember in minute detail exactly when they left; what they ate on the route; where they stopped over; and their fears and excitement, because this train journey was different from all others. It was a unique journey, which took them away from their families and homeland for the first time; therefore it deserves to be remembered with all its moments.

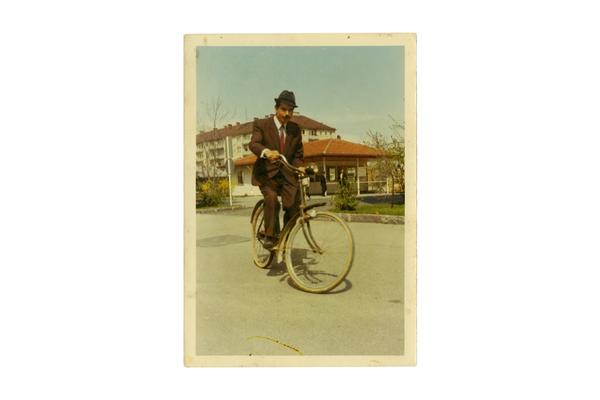

- European Identity: Felt hats increased in number in Turkey during the 1960s and 1970s. Workers, who had saved their wages and filled bags and suitcases with presents, set out in new European clothes for their first annual leave of absence. The felt hat became one of the easiest and cheapest ways to make a statement about being European and ‘having arrived’. During those years, if someone was walking along with a radio and a felt hat, everybody would know that the person had recently returned from being abroad.

“The suitcase means hope for an immigrant. We do not put it away under the bed or in a storage space. We keep it right before our eyes so that our hope stays alive.”

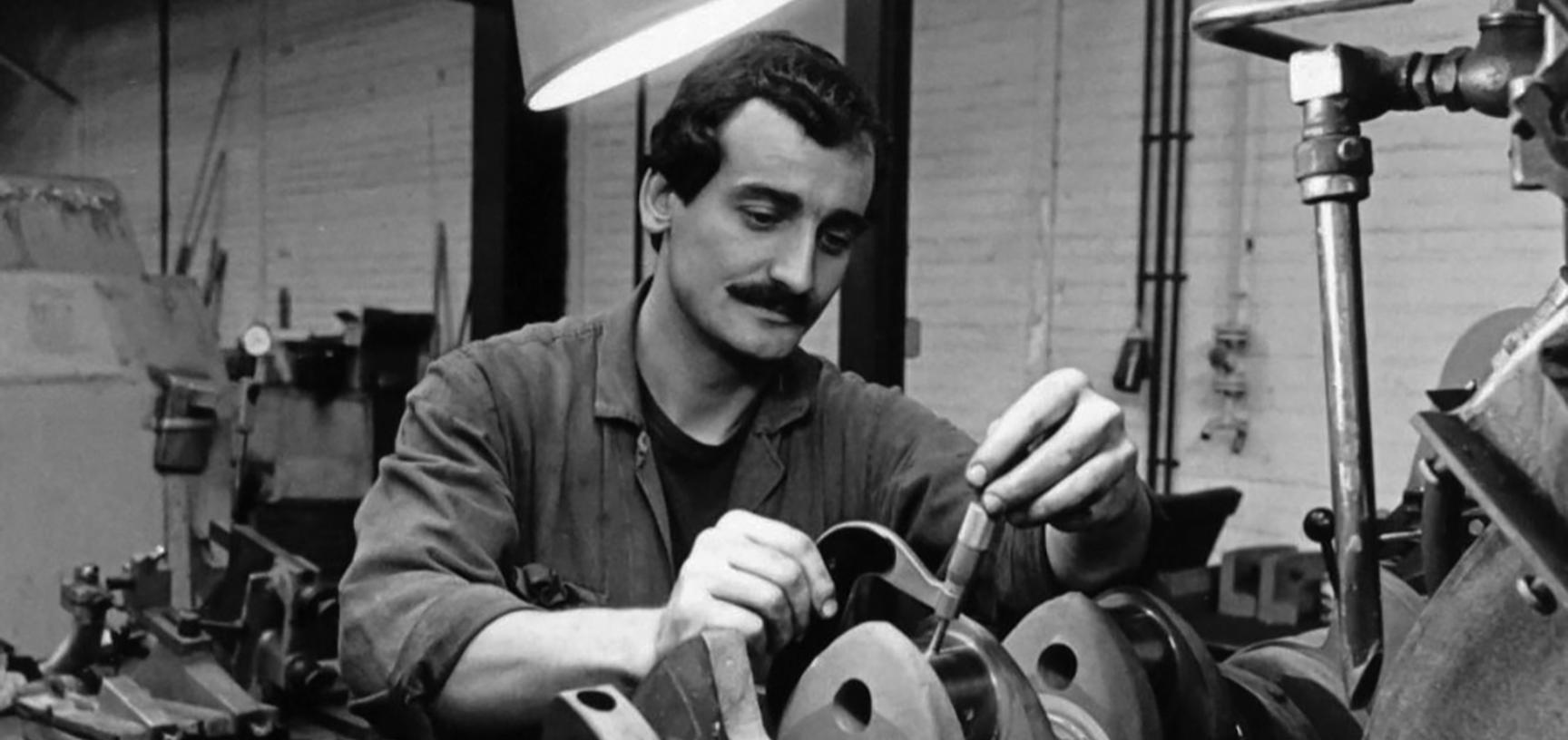

Work

- Permissions: The word ‘departure’ means a lot to immigrant workers and their families. This ‘documentation ritual’ starts even before crossing the border and continues for as long as they live abroad. It includes the work permit, the residence permit, other documents, stamps and official checks. As John Berger writes, ‘An immigrant worker is free only on his bed’ (A Seventh Man, 1975). Otherwise, workers live the daily lives that the documents designate for them.

- Guest Workers, Gastarbeiter: After the Second World War, West Germany decided to make up for a reduction in its labour force with foreign workers. The workers would come for two years; they would not be able to bring their families with them; and they would return to their countries when the contracts ended. These foreign workers were known as ‘Gastarbeiter’, i.e. guest workers. This term was used to eradicate the painful memories of war and to be hospitable to the newcomers. But although the workers were called ‘guests’, they were met only with overalls, miners lamps and digging tools.

“We don’t look like them, or they know we are foreigners. But when we go back to Turkey, I realise I do not belong there either.”

Living

- Voices and Moving Images: ‘One day, somehow we managed to get the Turkish radio station TRT. We were afraid that we could not find it again so we stuck the button of the radio to its spot with glue. Then it played some songs and we cried’, Turkish workers staying in a dormitory testified. Radio ruled for a long time. It was indispensible for every worker. However, in the 1970s cassette tapes started becoming popular, and radios were replaced by tape recorders. Recordings were called ‘voice letters’. The entire family and the neighbours back home would gather around to hear the scratchy but magical voice on a cassette. Later, these audio tapes were replaced by video cassettes.

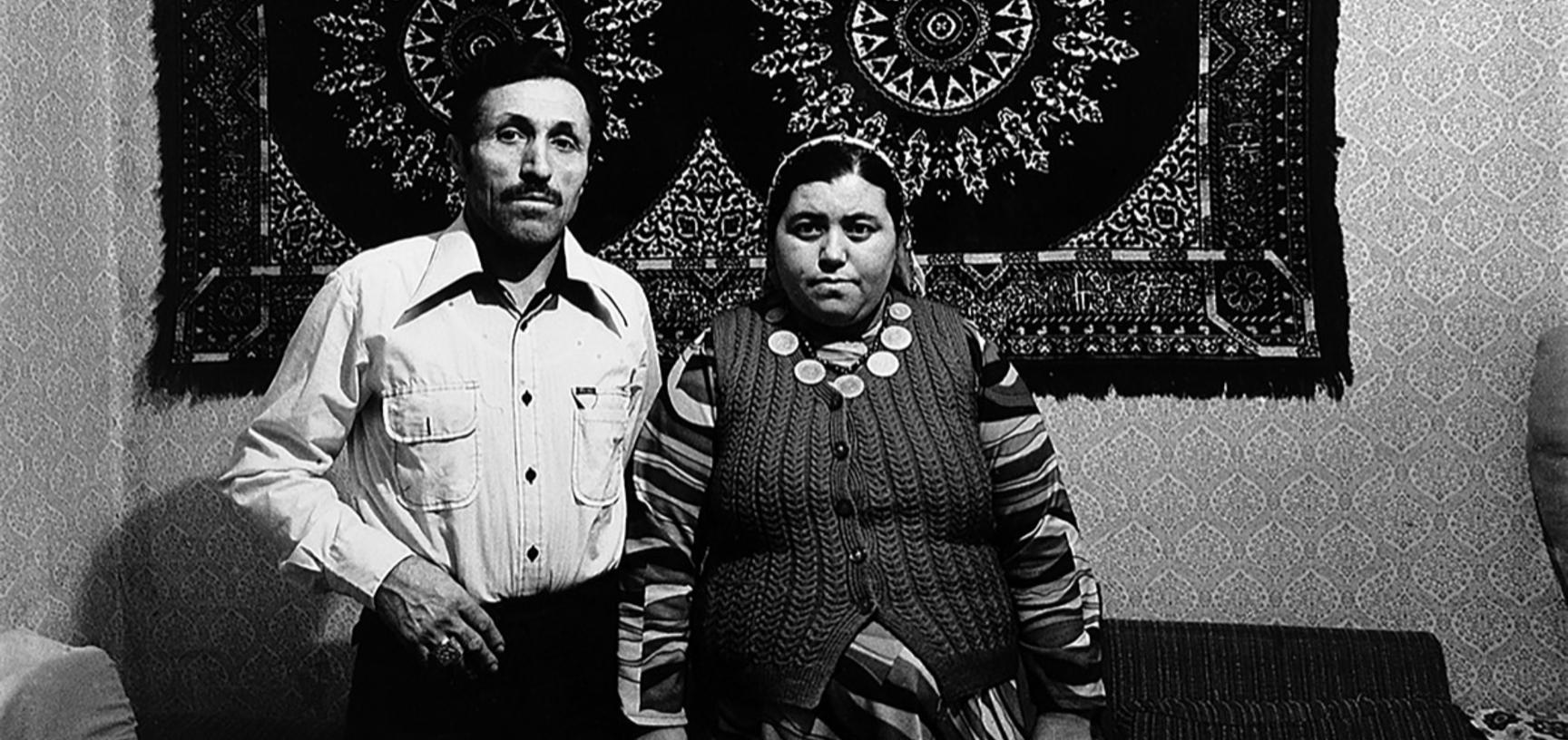

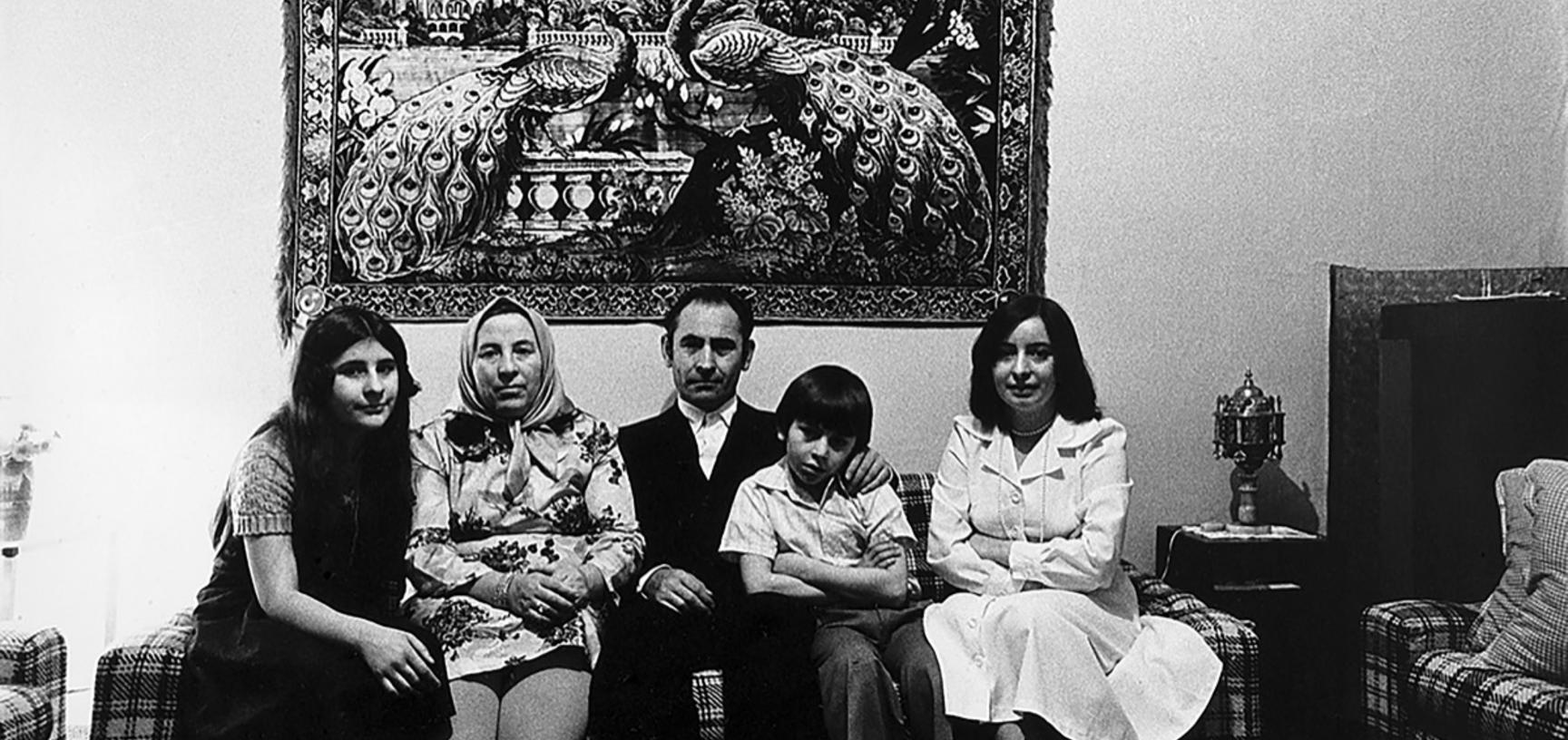

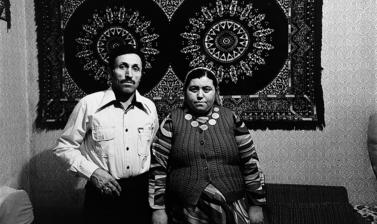

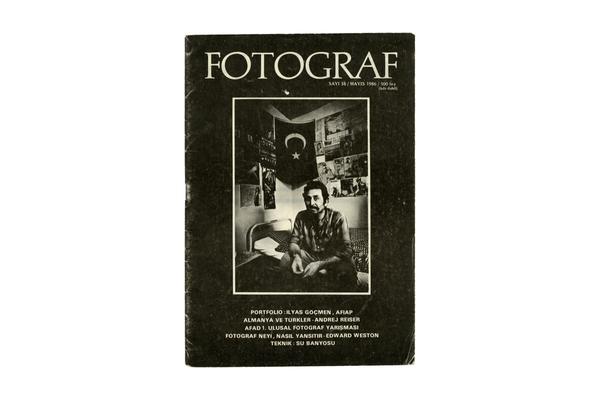

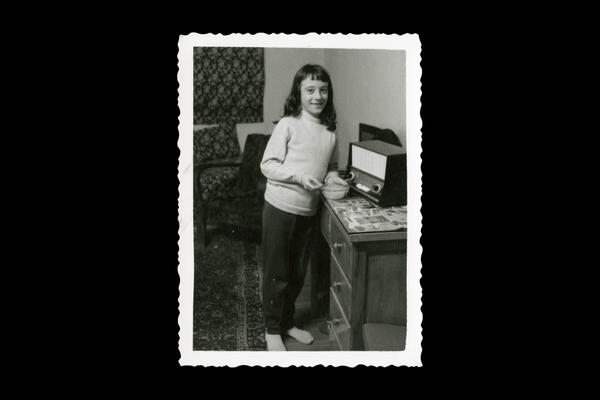

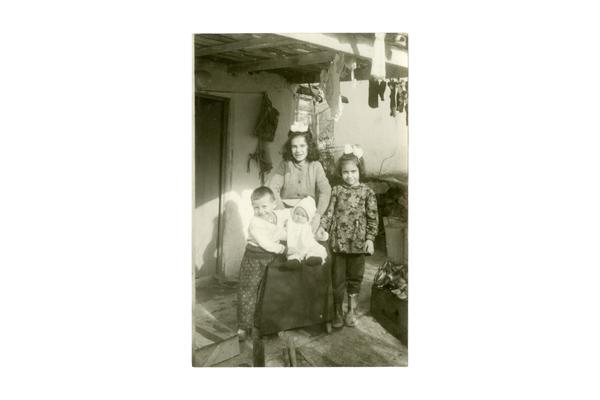

- Photographs: Every immigrant worker has a family photograph in his or her pocket. In this way they carry their spouses and children next to their hearts. Over time each print becomes worn around the edges and develops a crease down the middle from frequent use. This line gets deeper over the years like the lines on the palms of one’s hands. There is also a ‘traditional’ photograph which every immigrant has had taken with meticulous care and sent back home. The image has a meaning beyond capturing a ‘moment’ in the past. That picture, taken invariably in a worker’s best clothes and striking a positive pose, carries different stories for each of them.

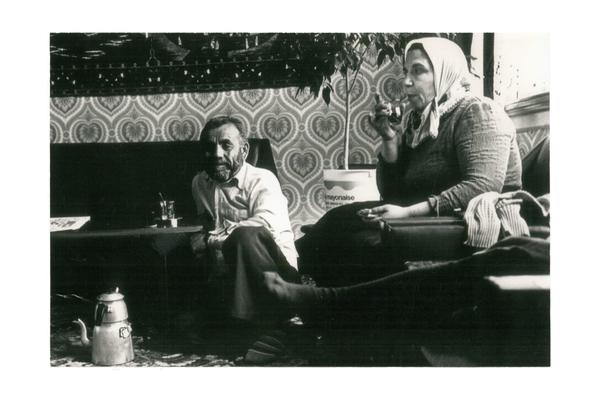

- Belongings: From the mid-1970s family reunions began, and the immigrant workers left dormitories and boarding houses to settle in their own homes. These houses were cheap, small and sparsely furnished, usually in the poorer districts of a city. As a ‘return to the homeland’ was still anticipated, workers thought they could put up with the difficult living conditions for a while. It was enough to be able to relax below a tapestry from their own country in the evenings. Husbands and wives intended to work in order to save more money and return home sooner. Even though the inhabitants were different, the immigrant houses all looked alike. Little furniture, a lot of hope.

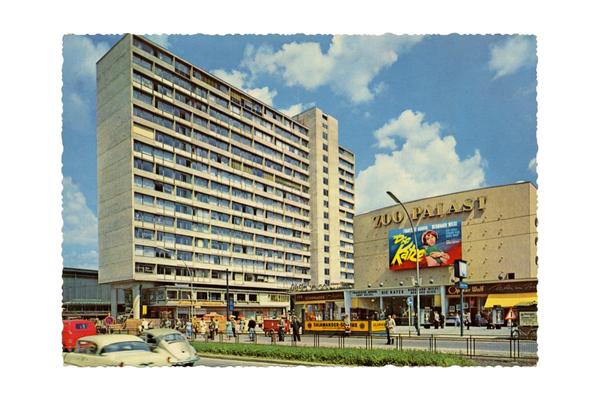

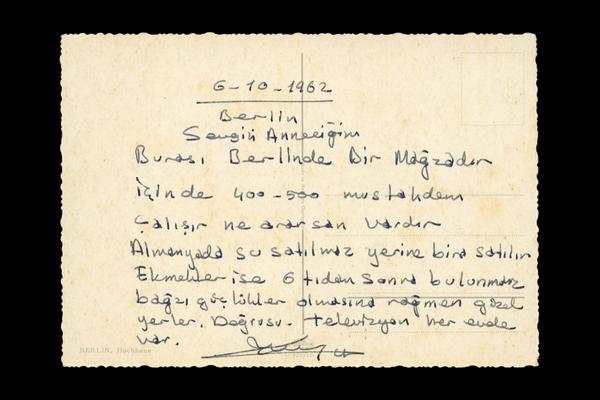

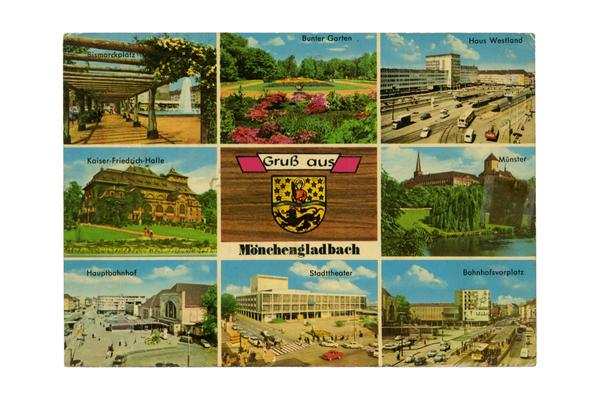

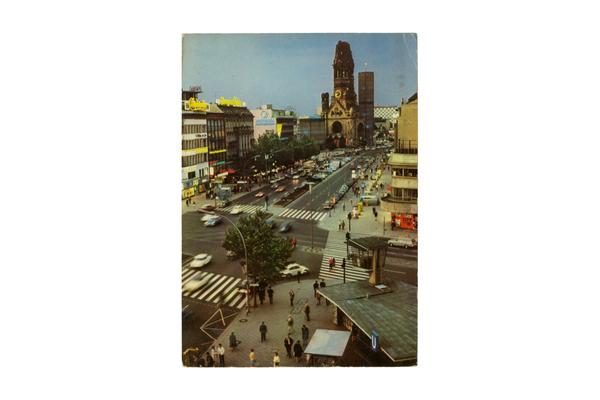

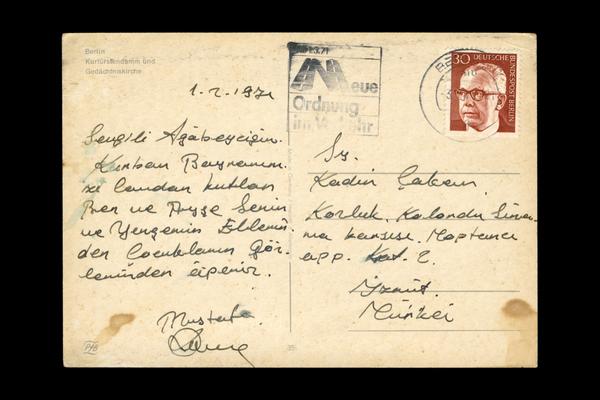

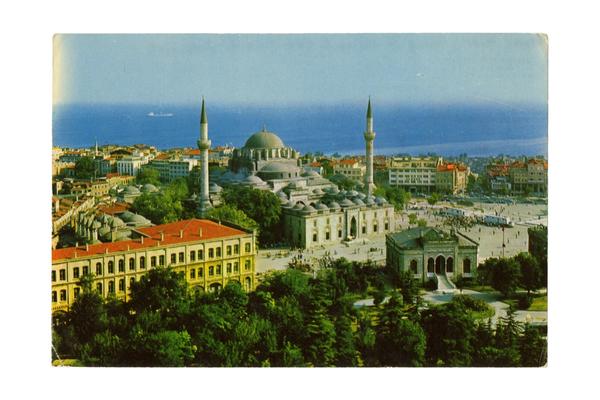

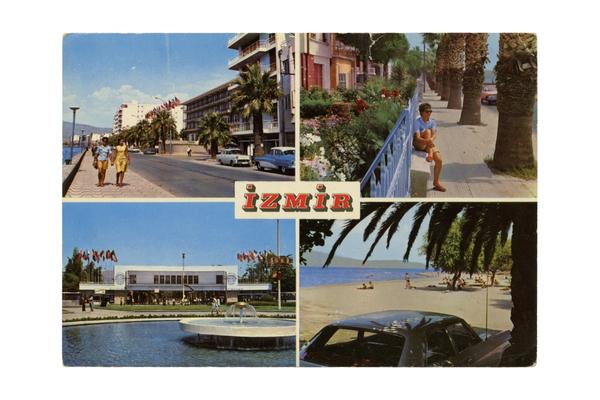

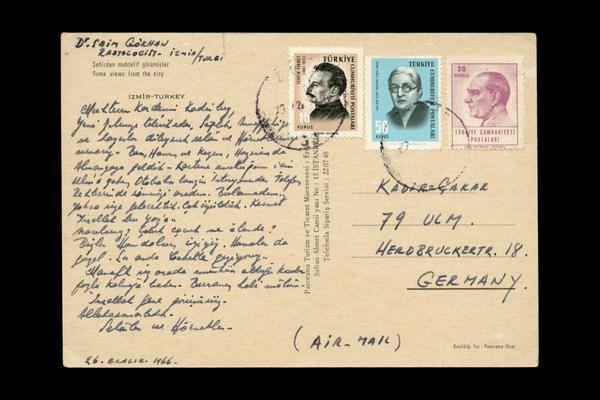

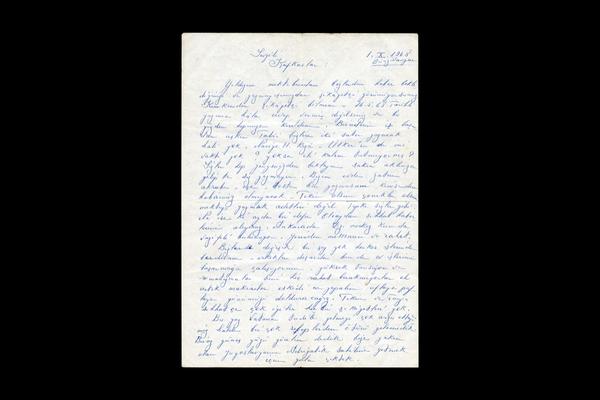

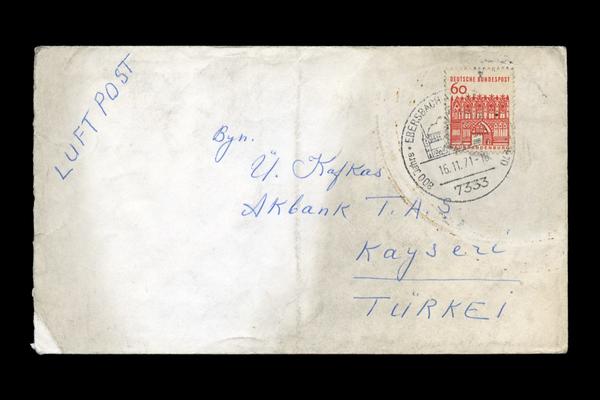

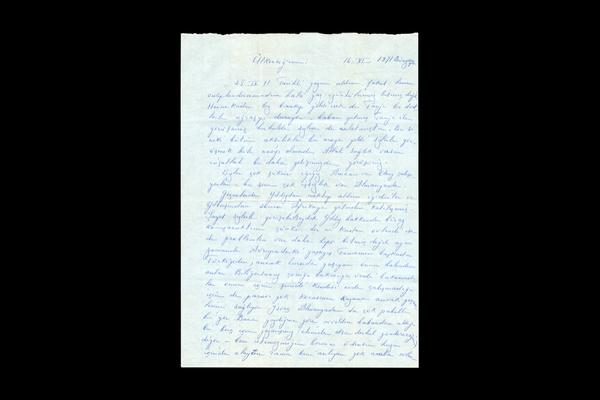

- Letters and Postcards: People in Turkey call those living abroad gurbette, or ‘away from home’. Those away from home eagerly anticipated receiving letters from the homeland for news of their loved ones. There were postboxes located at the entrances of dormitories, separated according to the different nationalities of the immigrant workers. Turkish workers took their post from a box labelled ‘Türkei’. It took about one month for a letter to arrive. Each new letter would belong not only to the person to whom it was addressed, but to everyone in the dormitory. They would gather around to hear all kinds of news from home, of the weather and the success of the harvest, of the children’s schoolwork and a new doctor in the village infirmary. Then it would be repeated for those who had missed the first round because they were working at the time of the reading. Letters were harbingers of magical words.

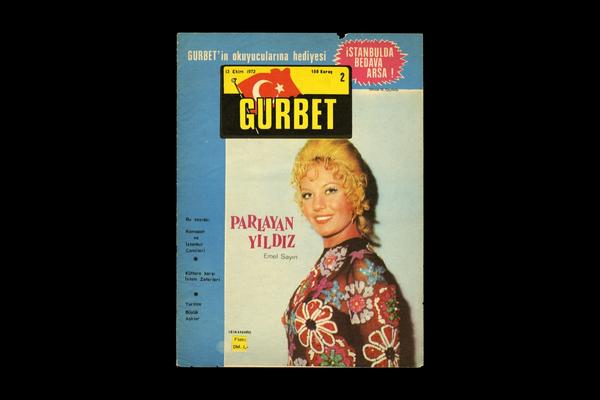

- Settlement: ‘When I started unpacking the boxes and using the things I had bought in order to take back home with me, I realised I would never be going back. Now they would be getting old with me.’ The 1980s were years in which the hopes of a return to the homeland dwindled, and permanent settlements started. A form of spatial as well as mental settlement began too. Shops, businesses, schools, courses, mosques and associations opened one after the other, as well as Turkish newspapers, magazines and radio stations – all meaning ‘we are staying here for good’.

“When I realised I would not be going back, I brought some soil and a sapling from back home. I planted it in a park in Berlin. Now I grow old in its shadow.”

https://player.vimeo.com/video/376536385?color=73070a&title=0&byline=0&portrait=0

Memoirs in My Suitcase (1) from Pitt Rivers Museum on Vimeo.

Acknowledgements and Credits

- Exhibition curated by ALART, DiasporaTürk, Philip Grover and Emre Eren Korkmaz

- Organised in collaboration with DiasporaTürk, Turkey

- Case and print design by ALART

- Conservation by Jennifer Mitchell

- Installation by Adrian Vizor

- Slideshow by Tim Myatt

- Special thanks to Bekir Cantemir, Gökhan Duman, Merve Genç, Aslıhan Kazancı and Yasin Tütüncü; and to the owners/lenders of the photographs, documents and objects in the exhibition: Ay family, Aygün family, Burhan Bektaş, Abdullah Belgin, İsmail Beyhan, Çakır family, Çelebi family, Çolak family, Şaban Dedeağaç, Delibaşoğlu family, Koray Deniz, DiasporaTürk Collection, Gündüz family, Kafkas family, Fatih Ketancı, Neng family, Müzeyyen Önal, Özel family, Özer family, Pakel family, Sönmez family, Şora family, Soyhan family, İbrahim Tenzile, Muharrem Tezer, Turhan family, Feramuz Türkan, Fikriye Ulusoy and Durmuş Zirgi

- Supported by Turkish Airlines

DiasporaTürk brings together volunteers and researchers to collect and share the stories and experiences of Turkish migrants living around the world, exchanging hundreds of photographs, personal stories and immigration objects. Through our social media accounts, we interconnect digitally with people living today in many different countries as well as in Turkey. Since 2016 we have organised three exhibitions – in Gaziantep, Berlin and Bursa – as well as related conferences and seminars to tell these stories of immigration and to understand the dynamics of the modern phenomenon of migration. You can find out more about Turkish organisation DiasporaTürk online here (Twitter) or here (Instagram).

You can watch an interview (in Turkish) about the exhibition with co-curator Emre Eren Korkmaz on Turkish television channel NTV online here (NTV).

You can join with the worldwide Turkish diaspora community on the Turkish-language YouTube channel +90, which was launched in 2019 by international media partners including BBC News Türkçe (YouTube), DW Türkçe (YouTube) and VOA Türkçe (YouTube). You can watch a documentary film, titled ‘Back in Time: 50 Years of Turkish Guest Workers’, produced by Deutsche Welle online here (DW).